Trump Grants Clemency to One of the World’s Richest Men

This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

In “Federalist No. 74,” Alexander Hamilton envisioned the presidential pardon as a “benign prerogative,” an act of mercy important enough to supersede all other laws. But clemency hasn’t always been used that way; sometimes, presidents like to get something out of it too (Bill Clinton, for example, was widely criticized for pardoning a fugitive whose ex-wife had donated to the Clinton Presidential Center). During both of his terms, President Donald Trump has marshaled that power for extreme ends, reserving pardons mostly for those in his political orbit, and rewarding loyalty and personal remuneration on an unprecedented scale.

This week’s pardon of Changpeng Zhao, perhaps the single richest person in the cryptocurrency industry, marks an escalation of that strategy. In 2023, Zhao pled guilty to violating anti-money-laundering laws during his tenure as CEO of Binance, the largest crypto exchange in the world. In a settlement with the Treasury Department, Binance agreed to completely exit the U.S. market. The company was also slapped with a $4.3 billion penalty, and Zhao was sentenced to four months in prison. Former Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen described Binance’s oversights as “willful failures” that allowed transactions involving cybercriminals, child abusers, and terrorist groups (among them al-Qaeda and the Islamic State) on the platform. Although Zhao has been out of prison for more than a year, he has been restricted from running the company.

Zhao’s newfound freedom is likely more than a happy coincidence. Binance reportedly helped create the code behind the stablecoin issued by World Liberty Financial, the crypto start-up that counts Trump’s three sons as co-founders. And in May, an Emirati-backed firm invested $2 billion into Binance using that stablecoin—a deal that exponentially increased the coin’s value. Although the White House has described the transaction as “totally unrelated to any government business,” the new relationship between Binance and World Liberty Financial could generate tens of millions of dollars a year for the Trump family and their business partners.

Zhao was not shy about his wish for clemency. This year, he embarked on a monthslong effort to lobby the White House for a pardon, working hard to ingratiate himself with Trump’s circle. In February, he hired Teresa Goody Guillén, a lawyer at BakerHostetler, who also represents World Liberty Financial and its CEO, Zach Witkoff. The New York Times reported that BakerHostetler works with a firm owned by the lobbyist Ches McDowell, a hunting buddy of Donald Trump Jr.’s; McDowell also reportedly lobbied for Zhao’s pardon. Cultivating the right friends seems to have paid off, even if the president seemed unable to recall Zhao’s name in a press briefing yesterday. (Trump called him “the crypto person,” and added that he was “recommended by a lot of people.”)

Zhao’s path to clemency is yet another instance of Trump reshaping the function of the pardon. Lee Kovarsky, a professor at the University of Texas School of Law, told me that Trump’s recent pardons tend to fall into one of two buckets. The first one encompasses overtures to Trump-affiliated groups, including political factions or particular industries that the president wants to keep happy. Trump’s pardon of Ross Ulbricht, who founded the Silk Road and was serving life in prison for overseeing a criminal enterprise, was the fulfillment of a promise he’d made to the crypto community before his second election. The second bucket, Kovarsky explained, is based on “venality”—the willingness “to pardon people that make large financial donations either to him directly or to aligned entities.” One possible example is Paul Walczak, the convicted tax cheat who was pardoned in April, three weeks after his mother attended a $1 million–per–head Trump fundraiser at Mar-a-Lago.

Zhao’s pardon is seemingly both a gesture toward a Trump-inclined industry and a response to the Trumps’ substantial profit from the May deal. Although Zhao’s future involvement with Binance’s business operations is at this point unclear, he has promised to “help make America the Capital of Crypto,” a clear echo of Trump’s own goal. And the president has little reason to slow Binance’s growth through regulation. Already, pundits are suggesting that his administration could unwind the penalties on the company and clear the way for its reentry into the U.S. market.

“Trump wants everybody to see what the returns on loyalty are,” Kovarsky said. This year, Trump has already granted clemency to former Representative George Santos (whose convictions include fraud and identity theft) and to the January 6 rioters, some of whom ended up breaking the law again after their release. “He is not the first president to issue clemency for personal reasons, but presidential administrations usually carefully administer commutations and pardons, in part to avoid recidivism,” my colleague David A. Graham noted in April. “The Trump White House, however, has shown little regard for the process.”

If history is any indication, Trump will keep using the presidential pardon to serve his own interests. By making clear that clemency has a price, he is charting a possible path to mercy for those who can afford it. Forget benign prerogatives—how about a check instead?

Related:

Today’s News

- President Donald Trump announced that an anonymous private donor has given $130 million to the U.S. government to help pay troops during the shutdown. The move is a possible violation of the Antideficiency Act, which bars federal agencies from spending money beyond congressional appropriations and from accepting voluntary services.

- Yesterday, Trump halted trade negotiations with Canada owing to an Ontario anti-tariff advertisement that invoked Ronald Reagan.

- New York Attorney General Letitia James pled not guilty in the federal mortgage-fraud case that Trump pushed the Justice Department to bring forward.

Dispatches

- Books Briefing: Maya Chung writes on the thrill of a great sports book.

Explore all of our newsletters here.

More From The Atlantic

Evening Read

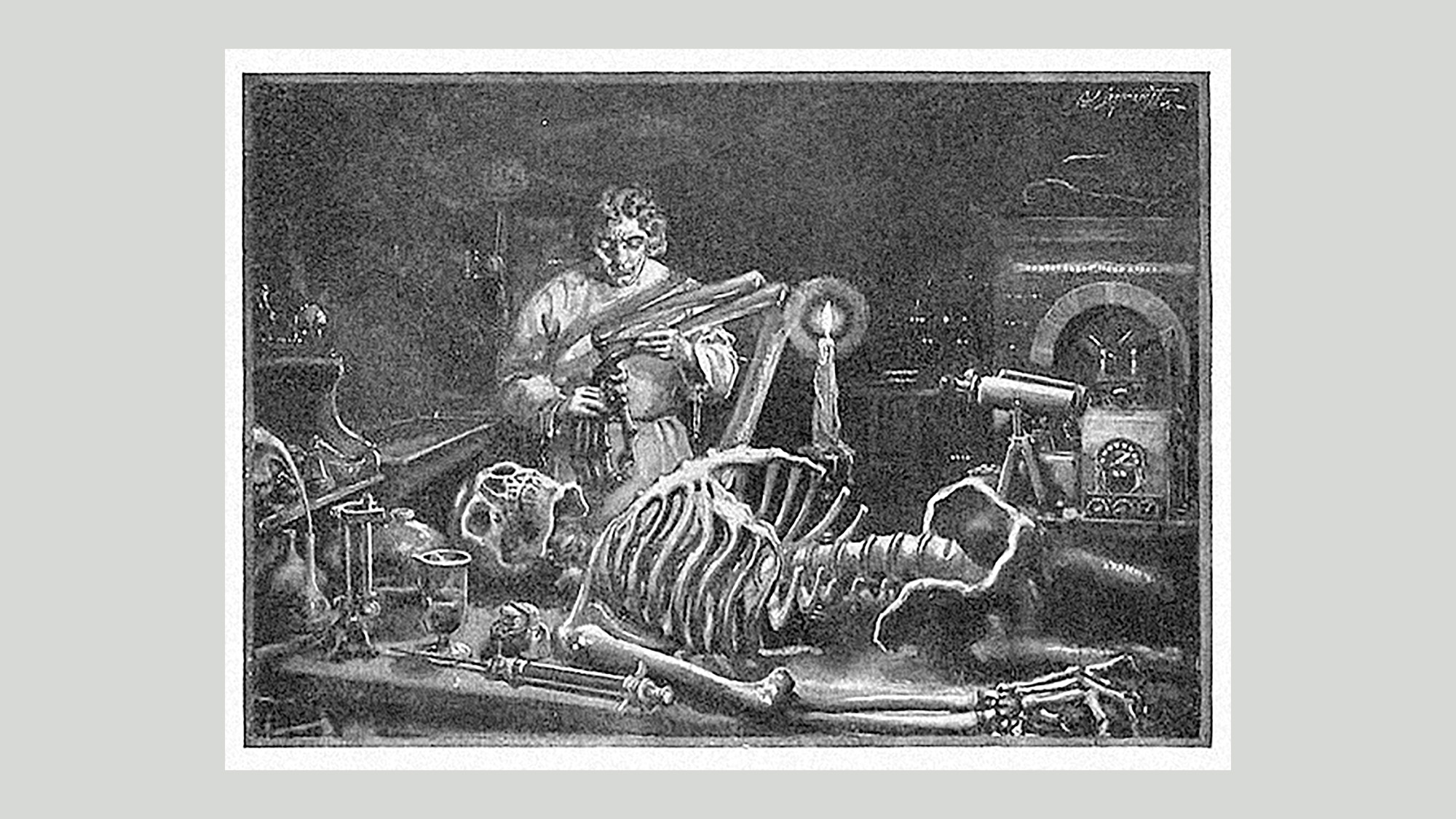

Why Guillermo del Toro Made Frankenstein

By Guillermo del Toro

To learn what we fear is to learn who we are. Horror defines our boundaries and illuminates our souls. In that, it is no different, or less controversial, than humor, and no less intimate than sex. Our rejection or acceptance of a particular type of horror fiction can be as rarefied or kinky as any other phobia or fetish. Horror is made of such base material—so easily rejected or dismissed—that it may be hard to accept my postulate that within the genre lies one of the last refuges of spirituality in our materialistic world.

Through the ages, most storytellers have had to resort to the fantastic in order to elevate their discourse to the level of parable. At a primal level, we crave parables, because they allow us to grasp impossibly large concepts and to understand our universe without and within. These tales can make flesh what would otherwise be metaphor or allegory. The horror tale in particular becomes imprinted in us at an emotional level: Shiver by shiver, we gain insight.

Culture Break

Watch. The Mastermind (in theaters) is far more successful as a character study than as a heist movie, Shirley Li writes.

Read. John Updike’s private correspondence was extremely John Updike. The Atlantic’s executive editor, Adrienne LaFrance, reads the author’s newly published Selected Letters and reminds us that no writer works alone.

P.S.

Thank you for sending in so many thoughtful responses after Tuesday’s newsletter about the Amazon Web Services outage. One theme among them that I didn’t address in the story: Students were widely affected when the education software Canvas went down. Other people—including the director of a nonprofit that focuses on horse care, who was unable to get supplies from Amazon for approved grant applicants—had trouble buying things online. Another reader was “saved from buying unnecessary stuff,” which: so true. We appreciate you all writing in!

— Will