‘I’m not as fierce as I seem’: Glenn Close on growing up in a cult, marching against Trump – and being unlucky in love | Glenn Close

Most of us don’t live our lives in accordance with a governing metaphor, but Glenn Close does. The 78-year-old was born in Greenwich, Connecticut, a town in the north‑east of the US that, to the actor’s enduring irritation, telegraphs “smug affluence” to other Americans. In fact, Close’s background is more complicated than that, rooted in a childhood that was wild and free but also traumatic, and in an area of New England in which her family goes back generations. “I grew up on those great stone walls of New England,” says the actor, chin out, gimlet-eyed – Queen Christina at the prow of a ship. “Some of them were 6ft tall and 250 years old! I have a book called Sermons in Stone and it says at one point that more energy and hours ran into building the New England stone walls than the pyramids.”

If the walls are an image Close draws on for strength, they might also serve as shorthand for the journalist encountering her at interview. Close appears in a London hotel suite today in a military-style black suit, trim, compact, and with a small white dog propped up on a chair beside her. For the span of our conversation, the actor’s warmth and friendliness combine with a reserve so practised and precise that the presence of the dog in the room feels, unfairly perhaps, like a handy way for Close to burn through a few minutes of the interview with some harmless guff about dog breeds. (The dog is called Pip, which is short for “Sir Pippin of Beanfield”. He is a purebred Havanese and “they’re incredibly intelligent”. Most dog owners in the US have the emotional support paperwork necessary to get them on a plane but, says Close, laughing, “That’s really what he is!”)

Anyway, none of this matters – neither the reserve nor the canine distraction – because, of course, Glenn Close is completely irresistible. How could she not be? The intensity of her most famous roles, from Alex Forrest, the “bunny boiler” in Fatal Attraction (1987), to her maniacal Cruella de Vil in 101 Dalmatians (1996), to Joan Castleman, the seething protagonist of The Wife (2017), makes her that rare thing, a movie star who is also beloved as a character actor. Long before A-list actors made a stampede towards television, Close was churning out five seasons of Damages, the great New York legal drama that ran from 2007, and her choice of projects remains improbably broad. After our meeting, she will fly to Berlin to film the sixth instalment of The Hunger Games, in which she will play Drusilla Sickle, then return to London to film Maud, a drama for Channel 4, all the while appearing on Disney+ in Ryan Murphy’s new schlock divorce drama, All’s Fair, in which she stars alongside – broad church, indeed – Kim Kardashian. Close, who has been known to lobby for a role after she has been turned down for it, has never won an Oscar, and if it’s a weird glitch in Hollywood history, from certain angles the omission works in her favour. Taken alongside the impossible grandness of a Meryl Streep or Cate Blanchett, Close remains the more nimble and interesting performer.

The Guardian

Actually, I suspect Close can be extremely grand in her way; she’s just better at clothing it in a down-to-earth manner. Her newest release is Wake Up Dead Man, the third Knives Out mystery by Rian Johnson for Netflix – first film, fantastic; second, a mess; this one, a return to form with a starry ensemble cast that includes Andrew Scott, Josh Brolin and Kerry Washington. (Brolin plays a Trump-like preacher in a small town in upstate New York, thumping his pulpit and leading people towards mutual hatred and suspicion.) Daniel Craig’s Benoit Blanc is funnier than ever (the best joke involves a snippet of music from Cats and some organ music from Phantom of the Opera). But the standout role in the movie is Close as Martha Delacroix, a righteous woman quivering with religious fervour – or “a sad character with no life outside the church”, as Close puts it – with the creepy habit of materialising behind people and making them jump.

The role was an easy yes for Close because of Johnson’s reputation. “I leapt at it!” she says. “I’d heard from absolutely everyone what a wonderful human being Rian Johnson is. And he really is. He’s incredibly bright and funny, and wonderful. I mean I’d marry him if he wasn’t already married.” Dry pause. “And if he’d have me, at my age.”

Poor Martha: stricken with guilt, fanatical to the core – a spoofy role, says Close, that “you have to play for real. If you try to be funny, you’re not funny. And the behaviour is funny because it’s written well.” It’s the quality of the writing that often draws Close to a project, and in this case, “Rian said he worked on the plot for eight months before he actually started writing”. Unlike the last Knives Out film, in which Johnson skewered the tech bros with a laboriousness that made the experience of watching it exhausting, the new movie takes on demagoguery without overtly wagging the finger. “It’s not making huge statements,” says Close, “and at the end, it’s like, order is restored and hope is possible.”

Close keeps a small apartment in Greenwich Village in New York – “where I started my career” – but her own source of hope and stability is her newish base outside Bozeman, Montana. This is where the actor’s extended family now lives – her sister and brother, who moved there in the 1980s, followed more recently by her older sister, and finally by her daughter, Annie, with Annie’s husband, Marc (the couple moved from LA and earlier this year had their first child). Close joined them permanently in 2019, and her wonder and enthusiasm for a tight-knit family, all living in one place – “It’s such a gift! All the cousins will grow up together!” – indicates how far it is from the way she was raised. But we’ll get to that.

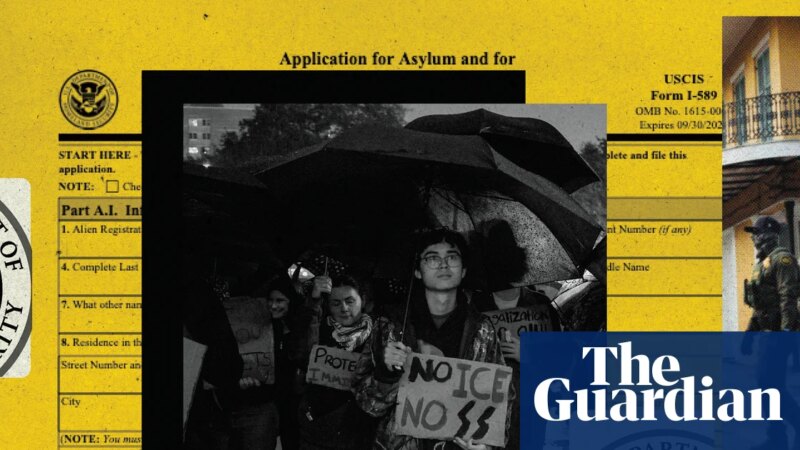

I tell her I have been on her Instagram page – she looks theatrically appalled: “I’m sorry!” – and was surprised to see photos she posted from a recent anti‑Trump, No Kings march in that part of the world, which skews heavily Republican and libertarian. “Yeah, it’s very red. We have a university in Bozeman, which is a blue island in a largely red state. So it was amazing that so many people came and stayed the entire time. They’d made their signs. I think everyone is just longing to be able to somehow let other people know how they feel. I’ve actually thought about going down to the courthouse with a sign.”

Montana’s reputation is deceptive in other ways, too. It is cowboy country – “Just around the corner from me is where Bob Redford filmed The Horse Whisperer,” says Close – but has long been popular with the ultra-wealthy in search of peace and stunning scenery. Michael Keaton has a ranch there, as does David Letterman; Ted Turner owns one of the largest ranches in the state. Close is living much more modestly and says she is working on finding her own community. “I’m not a hugely social person. But I have neighbours who I really, really like, and in my little community there’s a women’s club I’ve been to once and really enjoyed it.”

I can’t help but burst out laughing. The image of a Montana version of the Women’s Institute featuring Glenn Close on the cake committee is … unexpected. What do they do there? “People bring little cakes. The community will have potluck dinners. You get to meet Betty Biggs, whose family’s been ranching there for five generations, and she’s just a very interesting woman. I’m not somebody who would run to a ‘women’s club’, but I really enjoyed it, that sense of community.”

The other notable thing about Close’s social media feed is that the photos she posts of herself divide neatly into two categories: red-carpet ready and just woken up. For a movie star, and an older one at that, the 78-year-old is startlingly happy to appear bare-faced, hair puffing wildly off her head like “the endless work of dreaming”, as Marilynne Robinson once memorably wrote of a character.

“No makeup, yeah,” says Close with a sly grin.

Is that low-key political, the decision to appear unmadeup?

“I don’t think of it as political. I’m lazy. And I don’t think makeup necessarily makes you look better. It’s all about lighting. It really is. So I put a ton of light on my face and can look … OK. But, you know, I don’t want to spend that much time on my face if I don’t have to.” For The Hunger Games, she’ll be in makeup for two and a half hours a day. “So when you’re home you don’t want to have to do anything. I’d much rather be myself.” From an engagement point of view, it seems to be working – Close punches the air – “I got up to 1 million [followers]. I don’t know who they are, but thank you.”

If Close enjoys a tightly controlled version of letting go, it adds to her reputation as someone who, despite her status, enjoys sitting outside the entertainment bubble. I can’t imagine the crowd at the women’s group in Bozeman, for example, is particularly wowed by the actor’s Hollywood status. “No,” she says. “But then I don’t live a life that is saying, ‘Look at who I am, I’m a big famous actress.’ I never have. I have a little house in town and I sit on the front porch and say hi to people as they go by.”

The ability to derive happiness from small things is often most acute among those who were raised to take nothing for granted. For the first time in decades, Close is living near to her siblings, and one result of this arrangement is that they are able to pick over the carcass of their childhood endlessly. In fact, they talk about it “too much”, she says. Specifically: the abrupt change in circumstance that came about with their surgeon father’s decision, when Close was seven, to join Moral Re-Armament, a rightwing religious cult founded in 1938 by an American minister called Frank Buchman, and move the family from Connecticut to Switzerland.

Close won’t talk publicly about the details of the cult. She will only say that she still has triggers from the experience, which she has described as “a kind of psychological abuse couched in underlying misogyny”. Buchman’s movement posited what he called a “God‑controlled Fascist dictatorship” as a countermeasure to communism, and before burning out in the late 1960s it was weirdly popular – particularly in Britain, where its most famous adherent was Daphne du Maurier. When Close talks about her background, she focuses on the foundational years until she turned seven, which she characterises as happy and free, a case of she and her siblings running unsupervised around rural Connecticut. “What has sustained me is the landscape of my childhood, which becomes your DNA. One of my earliest memories is being on my grandfather’s farm in back country Greenwich, which was very pastoral then. And I just was a little feral child. My insides need nature.”

The regional stereotype of people from New England is similar to that of England proper: buttoned up, unshowy. “You don’t display yourself,” says Close, with a smile. “My mother – we all just adored my mother, and she was the most unmaterialistic woman ever. I never went shopping for entertainment and, now that I look back, I think it’s one of the ways that a girl could possibly start defining herself, if you go and shop. But I hate shopping.” If Closes’s mother was repressed, it was in part because, like a lot of women of her generation, she had neither the life nor the opportunities that, looking back, her daughter would have wanted for her. “Oh, I think she could’ve been an artist. She was really good at sculpturing. She could probably have been a writer.”

What did she do with that energy? She sighs, then bursts into rueful laughter. “Sublimated it to my father.” Close hoots. “Cooked! Cooked him meals that he would then eat in three minutes.”

Did her mother put some of that energy into shaping her?

“Oh, I was completely undefined for a very long time. I still am undefined.”

Maybe that’s better – to be undefined rather than rigidly holding to someone else’s mould. “Yeah, I guess so! You pull yourself together. You take all these bits and pieces and there’s … Martha.” Or Cruella, or Joan Castleman. “I’d like to think of it as confidence. I haven’t always felt that way.” It’s the process of piecing together the minutiae of a character that Close loves most about acting. “For example, the character I play in The Hunger Games, I started thinking about these little, tiny details that set off my imagination, and that’s where I like to live. This thing I’m going to do here [Maud, the Channel 4 drama]: same thing; I don’t have her yet. I do love that.” It’s the singularity of the chase that Close enjoys, but “it’s also collaborative. I have a wonderful wig guy, and [finding the character] will be a combination of hair, makeup, clothes. If someone can’t collaborate, they shouldn’t be in this profession. You can’t do it yourself.”

In her early 20s, Close got away from her parents and the cult to study drama and anthropology at the College of William & Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia. She was married by then, to Cabot Wade, a man she had met in a music and performance group affiliated with the cult and from whom she would separate within two years. She has said that acting saved her, although the impression one gets is that talent of equivalent size in any direction would have been enough to yank her out of that world. Life moved on, she became Glenn Close, but the memories and their impact remain. “It never leaves you,” she says. “It’s insane that what happens at a certain time in your childhood is,” she taps her chest, “right here.”

after newsletter promotion

So, too, the coping mechanisms developed in response. When Close talks about nature, or the soothing effect of returning in her mind to the happy first seven years of her life, it is with an unusual intensity. This is what I mean by her grandness; not in the sense of airs and graces or the affectation that runs rife in her industry, but a kind of operatic quality I suspect comes from the habit of having to get up the juice to overcome difficult experiences.

After college, Close moved to New York to try to make it as an actor. “I have a beautiful wooden troika,” she says, “which is [a toy] made of Russian smooth painted wood: three horses, a sledge and a man and a woman in the back under a rug you could take off and on. My grandfather got it from my uncle, who was killed in world war two, and it came to me and was my treasure. I used to play with it in the snow. When I first moved to New York and had my apartment, I’d gotten this cheap shelf and I put my troika on it and it collapsed. And the troika fell on the floor and all the horses’ legs were broken. And I remember I sank down to the floor and sobbed.” She pauses. “All the rejection I’d had, everything.”

She stayed weeping on the floor until something occurred to her. “It was the image of the stone walls. And I remember thinking: you get up. YOU GET UP.” She hisses it. “Get. Up.” Jesus. A real red-earth-of-Tara moment. Close got up and carried on.

The funny thing is, she says, in spite of this image of trauma surmounted, “I’m not as fierce as I seem.” She has said that Annie, her daughter, is fiercer. After her first marriage, Close married twice more, to James Marlas, a businessman, and most recently to David Shaw, also a businessman, from whom she divorced in 2015. In between, she had a relationship with John Starke, the film producer and Annie’s father. How is Annie fiercer, I wonder? “Oh, Annie would say [when Close was dating], ‘Mom, he’s an asshole.’ And I’d say, ‘Yeah, but he wasn’t always an asshole. I mean, why is he an asshole? What was in his childhood?’ She’d say, ‘Mom! He’s an asshole.’”

That feels like a very generational shift, from apology to no tolerance when it comes to bad behaviour. “Well, my daughter is all earth and I’m all air and water.” She smiles. “I’m not into all that but it’s interesting.”

Close is at her most formidable perhaps when she is pursuing a role. Several times in her career she has lobbied hard for ones she knew she wasn’t in the running for. When she auditioned for Fatal Attraction, she went into the audition knowing she was nobody’s favourite, and her soul “shrank to the size of a walnut”. To secure her role as Mamaw, JD Vance’s grandmother in Hillbilly Elegy, the 2020 adaptation of Vance’s memoir, she wrote the director Ron Howard a letter campaigning for the part. And in one of her earliest stage roles, the 1976 Broadway musical Rex, about Henry VIII, she messed up the audition. “So I wrote a letter and said I’d like to audition again, and I ended up getting cast as Mary Tudor.”

If one didn’t know better, one might suspect that this ability of Close’s to appeal to directors and casting agents to give her another chance is a highly effective audition shtick. “When I auditioned for a play called Albert Nobbs, which I ended up doing the movie of years later, I started auditioning and I just sucked. And I stopped the audition and said, ‘I’m boring myself to tears, so I must be boring you, and I think I’m going to go home.’ And at the end of that day, they called my agent and said, ‘That’s the most interesting thing that happened to us all day.’” She was, she says, “terrible at auditioning” and after that particular flameout hired an acting coach recommended by Kevin Kline. “And said to him I really want this part; and I worked with him, went back and got the part.”

On the subject of Hillbilly Elegy, the film and the book are now thoroughly tarnished by association with President Trump’s vice-president. Doesn’t the fact the film animates the origin story of JD Vance besmirch her memory of making it? “No. Not at all. Because I spent time meeting [Mamaw’s] daughter, or a niece, and looked at how she sat, talked, laughed, held her cigarette. What was in her house. I got very specific ideas. I don’t regret that at all. I think a lot of times a woman like that would be looked down on. And I also think I did her justice and I loved her.”

Given the amount of time Close spent researching Vance’s extended family in Appalachia, does she have any insight into why that part of the world pivoted so decisively to Trump? “I love reading history, and the great leaders through history were very eloquent people. We have not had … I think Obama was eloquent, but I was less and less aware of a kind of eloquence that you need to bring a people together. And I think you need to be sensitive to what people are dealing with. But you also have to be able to communicate with them. And I think people started to think that nobody cares.”

It isn’t the characters of Mamaw or Albert Nobbs, for that matter, that Close is most commonly identified with. Her most enduring role is almost certainly Alex Forrest, the book editor turned stalker who lit up the nightmares of every cheating man in the late 1980s and beyond. At almost 40 years distance, many of us who saw it as teenagers still remember vividly the most gruesome jump scares. And, says Close, “It really holds up. Kids are still watching it. I did some masterclasses in the theatre department of Indiana University, which is a wonderful campus, and before I did it I wanted the kids to see Fatal Attraction. They came in afterwards with their mouths open.”

Is the Forrest character, on whom the film heaped scorn in a way that today seems starkly misogynistic, still relevant? “I think it will always be relevant,” she says. “To me she’s a tragic figure.”

Which brings us, in a roundabout way, to Kim Kardashian. All’s Fair, the new Ryan Murphy drama for Disney+, features a roster of impressive women, including Naomi Watts and Sarah Paulson, and one slightly boggles at the idea of them acting alongside Kim Kardashian in her first major role. I would infer that the quality of the writing may not have been the main incentive for saying yes to this particular job – but it does sound as if it might have been fun. So … how’s Kardashian to work with?

“She’s lovely! And very smart. Very, very conscientious with her kids. When we were filming she was going through working towards her law degree, and near the end she would have flashcards. She now has her law degree, and I asked her: are you going to practise? And she said: no, I just want it in my back pocket.”

But I mean … she’s not got any acting background at all. “No. But she surrounded herself with really good people.” Close indicates herself and bursts out laughing. If that sounds arrogant, she says, “I swear to God, I’ve seen all nine episodes and it’s pretty fucking good. It is what it is: it’s juicy and outrageous at times and touching.”

What is so striking about Close’s current slate of performances is the amazing expanse of energy she is able to summon. I tell her I’m 49 and exhausted most of the time.

“Shame on you!!” she hollers. Well, yes. I don’t have your wall system, I say.

“You have walls all through your country!” I know, but Hadrian’s Wall doesn’t work as a metaphor for me. Anyway, the question is: how does she do it? “I’m energised when I have to be. I’m very good when I’m working, when I have a schedule imposed upon me. I’m not necessarily that good when I’m at home trying to figure out what to do for the next hour, because I always just want to read a book, and I know I can’t do that.”

It seems to me that Close has spent her life pushing through a determination to be happy. But I wonder if she thinks that ability is innate, or a function of sheer force of will? “Good question. I think when I’m with my family I’m very happy. I’ve been unlucky in love, which is sad. It’s not something that I’ve spent a hell of a lot of time thinking about, but I’m happy that my daughter has a mate for life. In fact, none of my generation in my family have been successful [in their relationships], except my brother. We’ve all had multiple marriages. But I think the next generation are much more … I think they’ve found life mates, and that’s fantastic.” She laughs. “But I … don’t mope around.”

“GET UP!!” I exclaim, startling us both.

“Get up,” hisses Close.